650-360-9309

By Gurpreet K. Padam, MD

Her perspective and my learning transcended a medical office, a memory I cherish. Patiently waiting in a chair, her frail, hunched-over body supported by a walker, she suffered from Restless Leg Syndrome. She rarely missed an appointment. Then one day, she failed to show up. When I called home, she told me what had happened. Her hello was weak. I asked, “How are you?” Because my daughter was sick today, she couldn’t bring me, and I couldn’t walk to the bus station”. Family members, partners, caregivers, and others in distress must mobilize resources quickly to get support and assistance. Psychological pain and significant illness are also common among adult children who support their parents. In all my years knowing Mrs. Z, she never mentioned her difficulties getting to the doctor. Instead, she arrived punctually and smiled. She told me she lives alone, so getting ready and leaving the house takes her all morning.

“My daughter has requested time off from work to bring me to my appointments. She lives two hours away, so it is a long drive. In the event my daughter cannot get me, I walk to the bus station an hour in advance. I get off the bus a few blocks from your office, and I have to walk to campus. No matter how much time I plan ahead, I worry about being late. It may take me longer to see you if I am late. I’ve already missed my ride. It gets dark early in the afternoon, and I feel unsafe waiting for the bus. It’s so cold. I get home a few minutes before supper, and the day is over.”

Her doctor’s appointment lasted 20 minutes and took up the entire day! Since then, I have been asking my elderly patients open-ended questions such as, “How are things at home?” or “show me a typical day?” We can gain insight into a patient’s daily activities and functional status during an appointment. An extra five minutes upfront can allow for a proactive approach and identify red flags. Since time in the clinic is limited, a phone conversation can continue after the patient leaves the office.

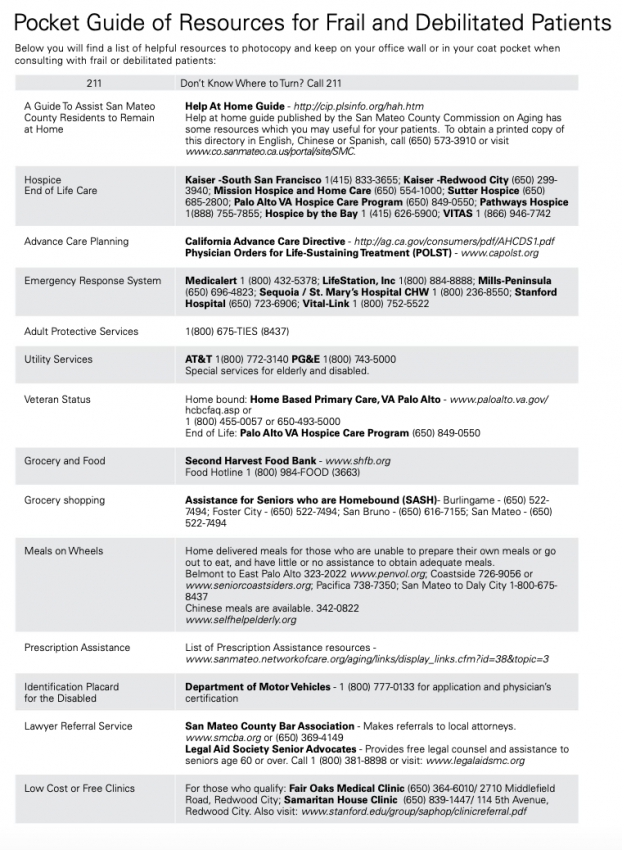

Mrs. Z was connected with resources to bridge her care gaps. Our efforts also included assisting her in maintaining dignity and independence. Mrs. Z was able to get a ride to her next medical appointment after county transportation services received our phone call.

She proudly fashioned a life-alert medallion on a necklace around her neck. Her fear of being alone in an emergency had diminished. The phone appointment we had about a year later revealed that Mrs. Z could no longer leave the house, even with the maximum amount of assistance. As her dementia progressed, she began using a wheelchair. Since Mrs. Z’s daughter lived out of town and had limited access to health care, she moved into a board and care facility in the area. This was so that she could be closer to her daughter.

We can refer patients who live outside the service area or need access to medical care to clinics or concierge medicine home-visiting doctors. When healthcare affordability or loss of coverage limits access to care, consider referring patients to community clinics, which may provide low-cost or free services to those who qualify. We can impact caregiver burdens, patient functionality, and independence by intervening. We are here to help our patients thrive and live healthier! Caregivers can provide better care when we assist in preparing them with the right tools, techniques, and support. Additionally, this can reduce the financial burden of caregiving and the physical and emotional strain. Both care receivers and providers benefit from intervention when equipped with skills and knowledge to manage their health and well-being.

Originally published: https://issuu.com/smcma/docs/smcp-feb2012, Edited for clarity: 1/30/2023. Updated pocket guide will be added soon.

Padam, G. (2012, February). Assisting Your Frail and Debilitated Patients, San Mateo County Physician, 1(1), 8-9,16.

1 Savla, J., Almeida, D. M., Davey, A., & Zarit, S. H. (2008). Routine assistance to parents: effects on daily mood and other stressors. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 63(3), S154–S161. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.3.s154

2 Lee C. Health, Stress and Coping among Women Caregivers: A Review. J Health Psychol. 1999 Jan;4(1):27-40. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400104. PMID: 22021431.

3 Cutland, L. (2005, November 10). Concierge’ doctors growing in valley Movement part of nationwide trend. Silicon Valley/San Jose Business Journal. Retrieved from https://www.bizjournals.com/sanjose/stories/2005/11/14/story2.html.

4 Scanameo AM, Fillit H. House calls: a practical guide to seeing the patient at home. Geriatrics. 1995 Mar;50(3):33-6, 39. PMID: 7883199.

5 Aberg AC, Sidenvall B, Hepworth M, O’Reilly K, Lithell H. On loss of activity and independence, adaptation improves life satisfaction in old age–a qualitative study of patients’ perceptions. Qual Life Res. 2005 May;14(4):1111-25. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2579-8. PMID: 16041906.

6 Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, Counsell SR, Stewart AL, Kresevic D, Burant CJ, Landefeld CS. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Apr;51(4):451-8. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x. PMID: 12657063.